What is the problem?

I do jujutsu and this is a martial art

that uses angle and position to gain

advantage and control an attacker's joints.

The system strives to use the minimal amount of force necessary

so that larger opponents can be dealt with. As such, it really has no

conditioning

component that is intrinsic to the training. Let me amke this clear: the aim is to

be clever about how people's bodies don't work to defeat them.

Some martial arts (such as boxing) rely on very high levels of conditioning

as part of their training. You will not find an out of shape boxer (nor

will you find many using it when they are 70.)

Take something like kung

fu which

is the generic name of several chinese martial arts.

Generally they have formal exercises called forms (these are

essentially

extended solo drills). These contains lots of awkward movements,

extremely low stances

and a variety of other things that make doing them well very difficult.

When you think

of 'funky oriental martial art' you are thinking most likely of some

form

of kung fu. Don't get me wrong, some systems really rock and

the people that

do them are top-notch, but I'm addressing how they put their

conditioning into their

systems. A lot of the movements in the forms are just conditioning

really. Think

of it as one-stop-shopping.

So why does jujutsu need some sort of

conditioning? First and foremost: to protect you against injury.

Strong limbs get injured a lot less. Most of the techniques in the system

do not require much power to do, but may require extremely high motor skills

to receive. Since you cannot really learn a grappling system without

experiencing it, the truth is that never receiving a complete technique in the system,

no matter how hard you practice otherwise, probably means you will never quite own

that technique.

Also, a major part of

grappling is getting the right body alignment to generate power in all

sorts of

weird positions as well as being able to smoothly switch methods of

applying

force. There just aren't many good ways to train that.

A correctly aimed conditioning program should make learning a system

easier. Also,

there have been times that I have not had a partner. Now, you can't do jujutsu

alone because you need to grapple with another person. All that happens

is you get

really bad habits that will get you thumped when you get back into

training.

So, in those times, I set about trying to get solo exercises that would

aid me, and make

it so I would be in shape with no bad habits when I could find someone

else.

Another reason is to recover from injury. I

have an

artificial hip.

I found myself in the unenviable position of not merely being out of

practice,

but being handicapped.

Taiso was perfect, being extremely scalable

and low impact. I was able to start at the barebones fairly soon after

surgery and work up

to sessions worthy of an extreme athlete. While I admit that I am

special (so my mother didn't

lie after all!) in that most martial artists don't have to contend with

this issue,

I really think that this alone would justify getting to know it. I have

consistently had

physical therapists compliment me on the excellence of my

rehabilitation. I follow their

guidelines to a 't' but always try to put it in the framework outlined

here.

By the way, I did taiso for years and didn't think of

putting more than a bit of it

into our class workouts. I only canvassed for more bodies after

I started a recovery program from hip surgery

and wanted some company (I admit it, I am selfish and it sure is easier

to do it regularly if

you have a few buddies there). I found out that what I thought was

pretty much run of the mill

was unknown. This has gotten such an enthusiastic reception all the way

around, I figured

I should write some of it down.

That is a really good question. There are

several issues with just doing this. Here is

a definition to get it all started.

Functional strength is the ability to use the total body

plus supporting

structures to meet specific demands placed on it.

What is behind this is the so-called Principle of Specificity,

that is to say

that the body will adapt only to those stresses placed on it. Said

differently (and this

is a mantra with some trainers) you only improve what you practice.

Functional training attempts to use the body

as a unit and stimulate the nervous system

to treat certain movements as atomic, i.e. to get used to

firing them from start

to finish. A lot of this thinking actually comes from rehabilitation,

where it is

pretty clear if a person lacks the ability to perfom a function such as

walking. Functional

training is aimed a movements, not groups of muscles.

Functional strength, while aided by

power,

is far from synonmous with it. Lifting weights

trains one type of strength (raw strength) in one plane of motion and

it does it very well. This is simply too optimized for a long-term

martial arts training program but can't be beat for getting stronger. Use it wisely.

There are two groups of people who train

with weights this section address. Powerlifters,

the people who train to lift huge amounts of weight, and body

sculptors/builders, who

train to reshape their bodies. I'll call these collectively lifters.

It is the powerlifters who make arguments about

strength training. Why not? That is their business.

|

|

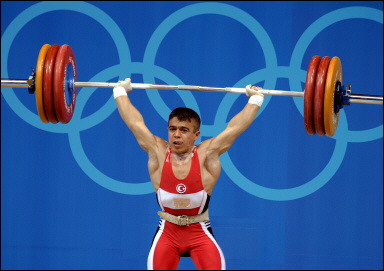

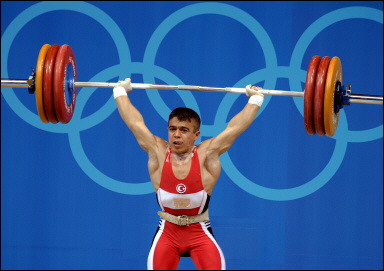

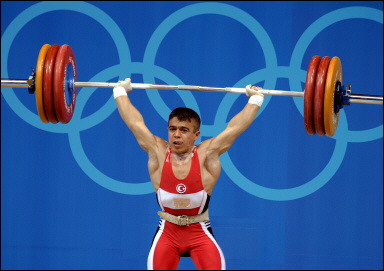

Halil Mutlu winning a gold medal in the 2004 Athens

Olympics.

A world class weightlifter. |

Stan McQuay A world class body builder. |

OK, for you purists out there, yes I know the difference between a

weightlifter and

a powerlifter. Weightlifting is an Olympic sport with two

movements, the snatch –

in which the weight is lifted above the head in a single movement – and

the clean and jerk – in which the first phase of the movement, the

clean,

brings the weight to the shoulders in one 'clean' movement before it is

thrust

or 'jerked' overhead. Powerlifting is another event that tests

the

squat, deadlift and bench press. I am trying to make a difference

between people

that lift weights to do something competitive with them vs. people who

compete

using the results of weight training. The former I collectively call

powerlifters here

while the latter I collectively call body sculptors – you won't see a

single

weight in a body sculpting competition. I should point out the

powerlifters

usually don't look all that different from other athletes in their

weight class. They

are certainly huskier, but

body sculptors do look appreciably different.

By the way, body sculptors only look

the way they do on the day of a competition, since a lot of 'showing'

relates to

balancing growth of new muscle (which also grows fat that hides muscle)

and dieting (which

loses muscle) down to a low enough body fat percentage (typically 6% -

8%) for the

muscles to be seen. It is not unusual for body sculptors to undertake

often

alarming dieting practices and such in the days before a meet.

Usually body sculptors will do a sequence of sodium loading/carb

depletion followed by a couple of days of carb loading with

diruetics. The idea is to cause the muscles to suck up a great deal of

carbohydrates and bloat, which makes thme look larger as well as

thinning the skin with dehydration. I know a couple of topnotch

competitive body sculptors and they all claim that the pre-show diet is

the hardest part of training.

A mistiming of a few hours will destroy the cosmetic effect. I'm

telling you this because if you think you will train in a gym and look

like a body sculptor on show day, you are sadly mistaken. Stan McQuay,

pictured above, is one of the very few genetically gifted

body sculptors who doesn't undertake extreme measures, simply reducing

his bodyfat during competition season. He is, of course, quite unique

in this respect.

Powerlifters tend to completely pooh-pooh

functional strength and state (quite rightly) that

strength is strength. This is mostly because statements about "functional strneght" are incomplete.

To use the term "functional training" you must supply the context. It must be functional

for a specific purpose and the more specific the better, e.g.

getting your floor fighter faster. This is why we have several types of strength is

ineffect giving a classification of functional modes.

Now on the flip side of this, I've seen guys who obsess about

bench pressing high loads, but lack the core strength to maintain form in a

pushup. The short answer to powerlifters is:

Powerlifting is functional training for something other than martial

arts -- in this case powerlifting itself.

The origins of these statements is ongoing chats with my powerlifting buddies who would say something

along the lines that "if you really want to get strong, come with me and do deadlifts". What I am trying to

do is counter this by pointing out jujutsu does a lot more than deadlift. Don't get me wrong, if you are

weak or have some imbalance of just want to be strong (if you are over 40, start powerlifting!) then definitely

do it.

There is nothing in powerlifting per se that will prevent you

from being

fast or smooth, but most people I've met don't have professional

training. So before you take advice from someone on lifting, be sure they

know what they are talking about. Pretty much every guy at the gym thinks

he is an expert in bench press. That said, here are some pointed reasons

why powerlifting alone is insufficient:

- Restricted range of motion The

range of motion must be severeley restricted if high loads

are to be lifted. This has to be the case to do this safely. There is a

reason there are only a

small handful of competitive lifting events. Moving loads in three

dimensions with a variety of

trajectories is not trained in any capacity. Said differently, of the

three possible planes of anatomical movement, powerlifting can only

train the sagital plane.

- Wrong conscription of fibers If

you lift a heavy weight, your muscle fibers kick in

as ST, FTA and FTB (look in the general

section for more about this).

We would like to have all the fibers conscript at once and this

requires some specific neural training

involving velocity.

- Constant improvement as a mantra. No. It is goofy to think

that you will be able to

add 15 - 20 lbs. of muscle a year indefinitely. This is just simple

common sense

but a lot of powerlifters don't consider it. The good ones take care to

cycle their routines and

have built in (aka "strategic") deconditioning, but these are the

minority in a gym.

For what it is worth, nobody has figured out why you cannot just pack

on muscle year after year.

So for example, adding a pound a week to your bench press would mean

that starting at 20 years of age and going until

you are 65 would have you adding 2,340 lbs. At some point you hit a

wall and can't get past it. However,

a carefully controlled study for adding muscle showed that there is no

difference in how much muscle

someone who is in their 20's can add vs. how much a person in their

60's can add. Both control groups

added the same amount of muscle over 12 weeks when using the same

training routine. Much of the wasting

that is seen in the elderly probably relates to inactivity levels as

much as anything else. Stay active

as you age.

If you think that you want

to bulk up then you should

consider cycling it in to your training. Be sure to stick with

compound exercises

like the deadlift, squat and clean and jerk and by all means find a

local club with good instruction if you get serious. Many of the lifts

are extremely technical (seriously!!) and just grabbing some large pile of iron is a

really bad idea.

Of course, some of people try to overcome natural

limitations by extrordinary

measures, such as drugs and hormones, which can't be condemned highly

enough. Food for thought,

a lot of people with asthma have to take steroids (such as Prednisone)

as part of their treatment. Even under the

care of a trained physician, I run into a fair amount who suffer joint

death, called avascular necrosis

and have to get artificial joints. You cannot do any heavy lifting with

most artificial

joints (although I've got one and can do taiso just fine and

this was one of the

big motivations for the way this is structured.) Don't do drugs.

Period. In any case if you hop on the constant growth bandwagon

you will eventually do what many a

weightlifters does and that is either burnout or find you have so many

joint issues (arthritis,

for instance) that your poundages have to drop. Then you have nothing.

We want something to

maintain certain skills.

Now for the body sculptors and why that is definitely a no-no. One

sculptor once went so far as to intimate that the goal was to look as

much like an erect phallus as

possible; odd thought that for female lifters.

They spend a lot of time doing isolation exercises to just get bulkier

and more defined.

If powerlifters train muscle groups,

body sculptors train muscles.

There are a bewildering number of these exercises and, being a gym rat,

I've seen body sculptors spending

as much as 3 - 4 hours working on some set of muscles. So in the time

it takes me to do my workout, run a martial arts class and clean up

afterwards they are still in there doing yet another of their

shoulder or pec sets.

There is nothing wrong with that, but here is the gripe: Many folks who

take up lifting do so without

clear cut purpose and end up sort of mixing up powerlifting and body

sculpting. They waste a lot

of time doing neither. Fuzzy goals give fuzzy results. They end up with

preposterous strength imbalances

that can be very hard to overcome. More to the point:

- Isolation exercises make you slow.

Every muscle that fires, called the agonist, has an opposing

muscle

called an antagonist. If there are not trained together and the

antagonist is quite

a bit weaker then it must fire longer to oppose the agonist. This is

just like having

a worn brake shoe on your car, you have to hit the brakes sooner to

slow down.

While proper training avoids

this, the odd fascination most people have with big pecs, biceps and

quads mean that these

are practically all that are trained.

- Isolation exercises make you weak.

When a muscle is in use (called in this

case a prime mover) it needs to have

muscles that act as stabilizers. If the stabilizers are weak then the

body will not allow

the prime mover to contract at full power less there be an injury. This

more than anything else explains why someone can, say, curl some

enormously

high weight on a machine but has trouble carrying their groceries.

- Isolation exercises can train your

muscle to misfire. The most famous

example of this is the leg curl machine. The hamstring is made to

straighten the hip when bent, although it also can bend the knee, being

one of the few muscles

that can act on two joints. This machine mis-trains the

hamstring to do leg curls which can lead to a higher incidence of

hamstring

rips. Sure, it makes the hamstrings get bigger, but you'd better not be

planning

on using them for much of anything else.

- It is a bald-faced lie that using weight machines is safer than using free weights. They allow

you to use really crappy form and body mechanics with no idea what is wrong.

The reason gyms have them is because the gym can hire completely unskilled workers at minimum

wage. All that most gym employees do is sweep around the equipment and clean it off.

Patrons use the machines which are supposedly safe. However, since the perception is that the

machine is safe, they misuse them, sometimes massively. One of the most grisly shoulder dislocations I ever saw was from someone

who was trying to use a pec fly machine with 60 lbs. on it! Since he was having trouble moving the weights,

he tried to use his abs in a massive situp to start the motion and his left shoulder came clean out of the socket (the

ball was by his ear. He went into shock as the hapless gym staff tried to ice it! Fortunately someone had

the good sense to call an ambulance.) I doubt seriously he could have done that with free weights.

My approach has been to think of conditioning as

maintaining certain skills for my

martial arts. These skills or types of strength are:

- Raw strength = How much you can move. This

includes how easily you can move yourself

- Speed = Ability to move you (or a load) fast.

- Agility = Ability to switch from one movement to

another. note this includes moving the whole body. You cannot be agile

if you cannot move yourself.

- Flexibility = Ability to move within full range

of motion with power

- Endurance - Ability to keep yourself (possibly with a small

extra load) in motion for an extended period of time. Swimming, running

are great examples, as are high rep squats.

- Explosive = Ability to set yourself or an

external load in motion quickly, includes plyometrics, sprints and such

- Isometric = Ability to hold a position with

maximal contraction either with or without an external load.

Working on these various types of strength is should drive your goals

for a workout.

The concept is that if you

have the basic motions down, then you can specialize them to a purpose.

Here

are the basic movements you need to train. These naturally organize in

pairs

that are given here:

- Shoulder flexion/extension: Standing

upright, raise your arm straight overhead/lower it

- Overhead pushing/pulling: handstand pushup,

overhead press/pullup

- Chest pulling/pushing: pulling something to

your chest/pushing

something away from your chest

- Pushing or pulling with the legs. squating

motions (includes jumping and swings) are pushes and deadlift type

motions are pulls.

Roughly, pushes are done mostly by the glutes, pulls by the hamstrings.

- Trunk flexion/extension: touch your toes/stand back up or tuck

into a ball and extend

All of these should be done with a torso twist

too, as well as unilaterally or bilaterally.

Finally, you can move yourself or an external load (this covers what is

called closed and open chain movements in training, by the way.) This

thinking of movement training is ripped off of gymnastics where it

has been shown

to be extremely useful. These were chosen because they are the basis

for most martial

arts techniques. To reprise my thinking, actual techniques require some

gross motor movement

that is done in a variety of settings and orientations and require

specific fine movements to finish. As it were, once the big movement is

done, techniques effectively happen from the elbows

or knees down. A lot (time-wise) of a traditional martial arts class

revolves around tutoring

these small movements, but there is no way that the large movements can

be trained independently. This eats up a lot of time and often it is

often not clear which part of a technique is what.

An example of this is the

standard hip throw in most jujutsu

systems. Students struggle with this because usually involves a

large squatting motion and they focus on this to the exclusion of all

else. The technique though is chiefly sending power through the grapple

and body placement. Having students do swings and double pistols makes

teaching hip throws a great deal simpler since they understand the

movement itself is quite distinct from the technique.

If we can get the

big movements fluid, powerful and well practiced, we can concentrate

on the hard (and fun) parts of the techniques. What's more, practicing

these large

movements can be done alone without screwing up techniques, as I

alluded to elsewhere. Don't forget we grapple, so you might not be

standing when you

must perform a technique. If we had different goals, we would have

different movements. For example,

we don't really kick much, so there are no motions for raising the legs

independently.

The last set of

definitions I want to add is to clarify our usage from other usages.

Standard usage is that an isolation exercise targets

exactly on muscle group, e.g.,

a seated bicep curl. A compound exercise

is one that uses more than one muscle group, e.g. a squat. Pretty much very taiso exercise is compound. We

refer to taiso exercises as simple that

is to say, consisting of one of the basic set (swing, side press,

push-up, pull-up, etc.) or complex which is some

combination of these simple exercises. A

complex exercise would be the swing + side press + windmill

combination, consisting of three simple exercises.

So what sorts of components do we need to control

to train our movements with the

appropriate skills? In no particular order, since they are all key I

list the following:

- Maintainability.

I want

to hit a plateau and stay there, since this is an adjunct to training.

I stress that

skills are just that, not attributes. Being able to bench press a

bulldozer is great, but if

you take a month off from training, that will go away. Therefore, you

must decide what

skills you want to have available at

all times and have a plan for keeping them

where you want them.

The measure of a good workout is

not that you are sore, but that you know you worked and how well you

feel you performed.

- Aleatoric training. The basic idea is

to have a compendium of simple exercises that can be knitted together

into complex exercises on the fly. This permits an aleatoric component

All together now, say 'a-lee-uh-TOR-ic', meaning that some

elements

are left to chance, unlike chaotic which means all elements are. No

workout should really

ever be repeated. Since I'm a geezer, this means I always look like I

planned it that way...

- Low weights. Movements with weights

are to be done with much lighter poundages than

standard weightlifting. I am very strong and use 50 lb. dumbbells, and

a beginner should use

25 lb. or maybe even 20 lbs. Paramount importance is given to being

able to move the weight

in three dimensions with control.

- Speed. The lifting rhythm for weights

is very different from powerlifting, since firing muscles

quickly automatically causes all fibers to conscript. You will be

moving much more rapidly

than you are used to and through a much larger range of motion.

- Avoid training to failure. Since the

emphasis is on compound exercises,

you should never do an exercise to

failure. The next set will re-use those muscles again, so if it is at

failure, you can bet

it will fail. This is unacceptable when, for instance, a full body

inversion is being done.

If you cannot complete your reps, stop and try later. Only aim for

daily totals.

- Use low repetitions in sets.

We often do just 10 or so for a given

exercise. Remember that

the exercises are automatically compound and we switch tasks often.

Don't let the

number of reps fool you! The cumulative effect can be staggering.

- Bodyweight exercises are integral.

There is also usage of lots of bodyweight.

This is done because agility is based on the ability

to move oneself. If you can't do a pushup, you probably can't do

groundwork since you cannot really

move yourself. Caveat just doing your own bodyweight isn't

enough, since you have to move things,

so the aim here is to get experience moving you and other

things all at the same time.

- All exercises are to be as complex

as possible. This mimics working with people

in training. Great exercises are those that use bodyweight and

dumbbells or partners (or all three).

- Cycle aerobic and anaerobic modes.

It's true that you will not need much

aerobic capacity in training, but what gets a lot of people is

switching from one mode

of operation to the other. Train this too, so your body is able to do

it easier. (Actually, this ups what is called your metabolic

fitness which is the ability of the body to provide

energy consistently to the muscle. It is metabolic fitness more than

cardiovascular fitness that is the major limiting factor to high

performance. The most recent work in training endurance athletes has

switched from just having them do their sport for longer times to

mixing in sprints and rests to up their metabolic fitness levels --

essentially what we do in taiso.

This causes you to grow more mitochondira, but I digress...)

- Task-switching is resting. Endurance

is increased by task-switching.

Since focusing on a set of muscles then using that same set at a lower

level forces the

body to recover faster, this permits you to effectively increase your

endurance of FT fibers.

Keep things zipping along nicely and switch tasks every

30 - 60 seconds. If you actually make a tally you are apt to find you

have done literally

hundreds of exercises from various angles for a body part.

- Tax your nervous system. One roadblock

for athletes is not muscular exhaustion,

but overtaxing the central nervous system.

That is to say, that for a compound motion, while the body has the

nerves in place to theoretically

perform the action, coordinating this is another matter. Think of it as

having too small of a

switchboard. Conscripting muscles the way we do it will force your

nervous system to get better

at using more fibers. Moreover, the aleatoric nature of the training

means that you will

be a lot more coordinated naturally when new and

bizarre movements are encountered.

A lot of weightlifters who have done this note that their poundages

actually appreciably jumped when they started taiso.

- Plyometric work is integral. Either

doing this with the dumbbells (most people only do

plyometric drills for their legs, not their upper bodies or abdominals)

or bodyweight. Most martial arts are explosive, so train that way.

If you are not familiar with this training, it runs

as follows. When

you load a muscle (think

of doing a squat; at the bottom of the motion the muscle is loaded with

your weight), the

fibers are a lot like rubber bands that have been made taut. Now, with

a rubber band, you can recover that

energy by releasing it. In the body, the fibers can release it by

moving or if not allowed to move, by getting hotter. If you immediately

contract the muscle as soon as it is loaded, then you get that energy

back before it dissipates as

heat, plus whatever power the muscle can generate. This is why

basketball players bounce before doing

a high shot. We actually use this when we strike or throw, so getting

your body used to this with

all motions is a grand idea. Plyometric training for track is now

standard because it has

been shown to be so successful.

- Partners are the perfect training equipment.

Two partner drills are included as well, where one person gets practice

stabilizing with

their core muscles as the other does an exercise. There are few better

ways to get all

of your core utilized than having someone climb over you. This is core

training with a vengeance.

- Be a cheapskate. Really fancy

equipment does a lot of the work for you usually,

so I tend to avoid it. Exercise machines do have their place though,

either to rehab an

injury in a safe way or to compensate for a strength

imbalance/deficiency.

- Vary

Exercises. As I stated above, there are only so many motions.

Work within that framework as a basis for training and hit every

motion. You can do them with a twist, unilaterally (e.g. one-legged

deadlifts, one-handed pullups), bilaterally (two-legged deadlifts,

standard pushups), as well as body weight and weighted exercises.

Finally these can also be done as open or closed chain exercises too. (Open

or closed

chain is a fancy way of stating if the limb where the load is

moves or is fixed. A handstand pushup is closed chain since the hands

stay planted, but an overhead dumbbell press is open chain. ) A goodly

compendium of movements constitutes a workout. You are limited only by

your inventiveness here.

As an aside, by using smaller weights you get a

feel for how

to move with control and power against a manageable resistance.

A cornerstone of our art is yielding to an overwhelming

force and redirecting it (this is the ju is jujutsu).

If you experience a

force that is higher than what you experience in taiso you are

in over your head and

should switch tactics.